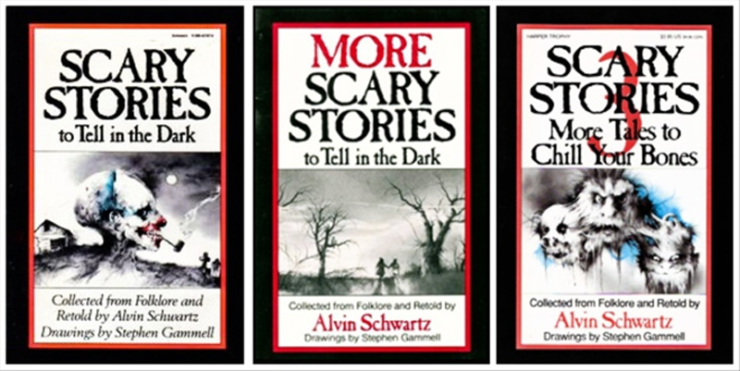

Author Alvin Schwartz and illustrator Stephen Gammell have a reputation for teaching a generation of kids to fear the dark. They didn’t. Instead, their series of Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark books taught children to love the dark, to be thrilled by it, and to use their imaginations to populate it.

The pair also gave young readers lessons in identity, in getting to know their own character. I remember kids on the playground or at birthday parties trading details about their favorite stories from the books. Some kids were most disturbed by the body horror of a spider laying eggs in a girl’s cheek, while others related to hallucinatory confusion of a woman on vacation who fetches medicine for her sick mother only to return to her hotel and find every trace of her mother erased. What scares us is as personal to us as anything else—it tells us who we are.

And yet “Harold” is, no question, the best story of the bunch.

For those of you who haven’t read the last of the three original Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark anthologies, the story starts with two farmers, pasturing their cows in the mountains for the hot season; they are isolated and bored. They make a doll—a scarecrow, basically, that represents “Harold,” a farmer they hate, and spend their evenings humiliating, abusing, and taunting it. When it starts making noises, they chalk it up to nothing more than a mouse or rat moving around inside the scarecrow’s stuffed interior. One day Harold, the strawman, gets up and shows them, in various ways, that he didn’t appreciate his treatment at their hands.

The story is one of the most technically accomplished of the series. The Scary Stories books draw heavily from folklore and urban legends; these certainly aren’t bad sources, but they do involve a lot of inexplicable behavior, like a character deciding to eat a big toe that they found in the dirt. “Harold”, by contrast, is a narrative that succeeds in building character and atmosphere in a clear, logical way. We meet the characters, understand their boredom, and begin to see the uglier side of their natures as they come to abuse the effigy of the person they hate.

The story also does a strong job of using bizarre details to build dread. There would be no suspense if Harold suddenly popped into consciousness and chased down his tormentors. Instead, the scarecrow’s moment of awakening is the creepiest point of the whole narrative. The book describes how he walked out of the hut, “climbed up onto the roof and trotted back and forth, like a horse on its hind legs. All day and night he trotted like that.”

Meant for children, these stories are compact—few of them are more than five pages. In just two sentences, this story builds an uncanny horror that forces even the most unimaginative reader to think about what it must have been like for the two terrified farmers, huddled inside, listening to that thing scrambling back and forth on the roof all night long. When the farmers decide to make their escape, we applaud their good sense. When one of them has to turn back to retrieve the milking stool, we’re as sick with apprehension as he is.

Buy the Book

Middlegame

And yet, imagine how disappointing and anticlimactic the story would be if both the farmers had simply left and that was that… We need something to happen; we want the story to keep building toward its terrifying conclusion, which is exactly what we get when the fleeing farmer turns back from the nearest vantage point to see Harold stretching out his unfortunate buddy’s skin over the roof of the house.

This ending underscores the larger point of the story, the point that makes “Harold” more interesting than any sketchy urban legend or quick jump scare: It brings home the fact that we want to see those characters suffer, just as those characters wanted to see Harold, the rival farmer, suffer. Of course, we tell ourselves, it’s just a story. We’re not actually hurting anybody. Then again, neither did either of the characters. They let their bad sides take over, gave in to their darker impulses, using what seems like a safe, harmless outlet… and what did it get them?

It’s poetic, then, that “Harold” has undoubtedly kept many readers up nights, over the years. What story, in any anthology anywhere, better illustrates the fact that we create our own terrors? We come up with them, we encourage them, we strengthen them—and then we’re surprised when they take on a life of their own. The horror reader bolts upright in bed whenever the house creaks at it settles around them. The person who can’t get enough true crime inevitably has to walk to their car along a deserted street late at night, heart pounding. The vicarious thrills we seek in scary or violent stories can take a toll, if you’re not careful and self-aware. “Harold” holds up a mirror to the young horror fan, and whispers a warning: You carry your worst nightmares with you—be sure that they don’t take hold of you, instead…

Esther Inglis-Arkell writes about history, science, pop-culture, literature, and everything that makes life interesting. She currently lives in San Francisco, where she chronicles the things library patrons have scrawled in the margins of books. You can follow her on Twitter at @EstherHyphen.